Episode 14: Bryce Jacobs

Adam Burke: Welcome to The Cockatoo, reporting on what Australians are up to in music in the USA. My name is Adam Burke and we're coming to you from Hollywood, California, which is Tongva and Chumash country. In these interviews, we get into musical journeys to the United States. Today we are joined by composer, multi-instrumentalist, and inventor, Bryce Jacobs. A graduate of the Sydney Conservatorium of Music, Bryce has worked on film and TV titles including Happy Feet, Australia, P.S. I Love You, Pirates of the Caribbean, Rush, Man of Steel, 12 Monkeys, Skyscraper, Christopher Robin, and Daybreak.

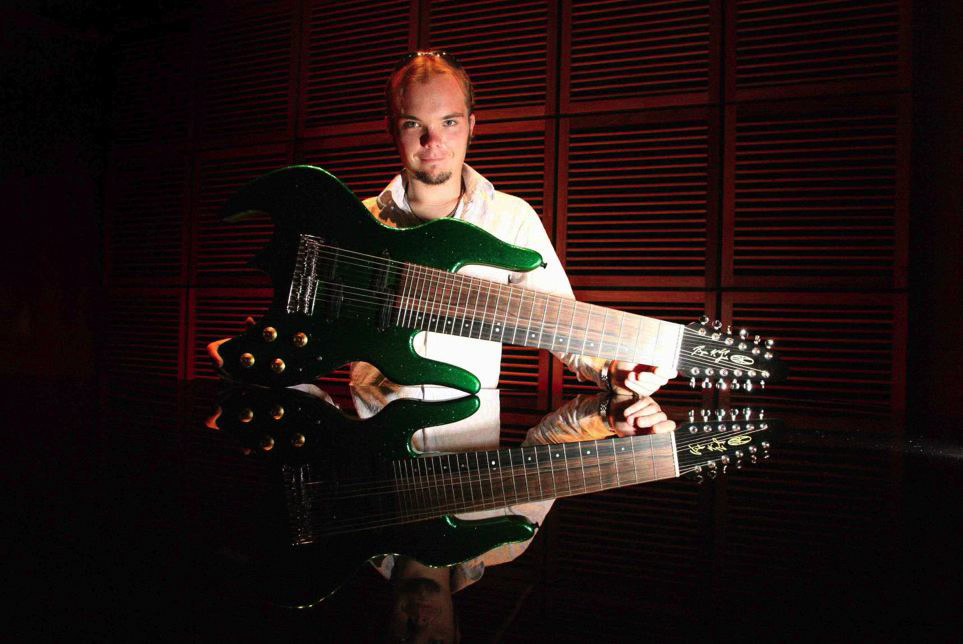

He's been a part of the creative team at Hans Zimmer's Remote Control Productions and has also composed for video games, including Call of Duty and Medal of Honor. In addition to all that, he invented a seven-octave guitar based on the range of a piano. Bryce joins us now from his studio in San Fernando Valley. Welcome to The Cockatoo.

Bryce Jacobs: Thank you. You make me sound a lot better than I would put it.

Adam: I only touched the surface of what you've been up to, but let's start off with a little bit of background. Where'd you grow up?

Bryce: Sydney in the Sutherland Shire, which sometimes people hold against you, but it's a beautiful area of Sydney.

Adam: Got it. When do you remember first picking up a musical instrument?

Bryce: I was given like a basic keyboard, which had an engine on it. It was like this two-octave thing that you turn on, it was very basic. Then I think my grandmother gave me a violin to muck around on. The first guitar I was ever given was this one of those toy plastic things. I was so embarrassed about playing it, I'd go in the garage and play it and, I'm in a converted garage now, so nothing's really changed.

Adam: We're going to do a real fast forward here. When did you move to the United States?

Bryce: 2008. I'd been here a couple of times before, but 2008 is when I came here and tried my luck, seeing if I could dig up something on the film composer side. Five hours before getting on the plane on the 89th day of the 90-day visa waiver, I landed a job with Ramin Djawadi, who's based out of Remote Control Productions, which is Hans Zimmer's place and packed up life and wife and moved here at the start of 2009 and started on that journey underneath Hans' studio roof.

Adam: At that time in 2009, when you moved, what was your circumstances? How did you manage it? Where were you in your life and what did you have to make happen in order to move everything across the Pacific to the US?

Bryce: I'd just finished working as a touring guitarist for singer-songwriter Josh Pyke. It was quite a contrast because at the start of 2008, I played all the big day outs with them, which, very cushy with the parties, guitar tech, great hotels, and all that kind of stuff. Then coming over here, then I'm making coffee and getting lunches, and somehow I was just taking daughters home from ballet and all this kind of stuff. Somehow I was happier doing that. The problem was the financial crisis kicked in. Then on the worst day, it was $0.52 Australian to the American dollar.

I had to exchange my money to pay the legal fees for my immigration lawyer and literally lost half my money in the transfer. I think, what did I have, $10,000 went to $5,000, just like that. We started off pretty humble when we came over here. When you start off as an assistant composer, I think at the time it was like $2,000 a month. Was very scarce. Thankfully, my wife got a job, probably one of the only jobs going pretty quickly into her coming here and she's done great ever since. We started humble.

Adam: Yes. I think at that time the exchange rate was all over the place. It went from $0.52 and then later on it went up to over a US dollar for an Australian dollar, right?

Bryce: Yes. I know. That was the first time since the early '80s or late '70s, but I never thought I'd see that happening. That would have been the day to exchange.

Adam: Absolutely. Had you made the decision to move to the US before that crash of 2008 came or did that happen right in the middle of the time you were moving?

Bryce: It happened right in the middle of it. I was staying at a place called Tilden House. I don't know if it still exists in the same way, but Christopher Young very graciously would rent out this house, like four rooms in the house for four months for four composers, I went there and at first, I was paying like $100 a week. It was about $400 a month and Australian, it was 425 or 450.

When the financial crisis hit, all of a sudden that was 700 and something Australian dollars. It was an instant like my rent nearly doubled. It was cheap rent though, so I can't totally complain, but I had a deathtrap of a car at the time and, I wasn't making any money. They were giving me gas money and I was working for free.

Adam: What was your feeling that motivated you to move to the US? You were in Sydney at the time. What was it that made you want to just pack everything up with your wife and head across the Pacific?

Bryce: The music industry in that period of time, as we all know, was a very weird place and it was just a bit of a mess. I'd realized that what I fell in love with, like Zeppelin and Floyd and, like up until the early 2000s, there wasn't that reckless abandon you could do with music. Whether it's dance or rave music or even jazz, it just seemed that things were so careful then. Film was like the last place you could go and have a bit of a-- you could do anything you wanted as long as you were serving the story.

That meant stylistically totally, anything is fair game. Yes, after all these years in the music industry, I could see as I was coming into the film industry that it was going to be even harder. I'd only done two short films at that time, and I'd done the orchestrating. I thought, "I'm eventually going to probably end up in America anyway. Why not just pull the plug and see what happens?"

Adam: Then at the time that you came across to the US, in addition to being a session and touring musician, you'd also done a little bit of work in film, right?

Bryce: Yes, thanks to Jessica Wells, who was my-- because I did a composition minor initially in my performance degree and then somehow was able to get into it as a master's. She was like a student lecturer at the time when I was 18. She's in her early 20s. I don't know how it came up. I think it's because I designed the guitar. There was a film called Gabriel. Shane Abbess is the director, an Australian film. Brian Cachia was the composer and I was in a band with him and he saw this guitar I designed.

He said, "Oh, do you orchestrate, because I'm going to need an orchestrator." I'm like, "Yes, I'm thinking of university goes." "How much do you charge? I'm like, "I don't know. I've never charged for it before." I asked her because she had a orchestration business at that time. I asked Jessica Wells and she said, "Look, if you're looking for that kind of work, I've got a film coming in, penguin that can dance but can't sing. I started copying parts on that and then it led to orchestrating with her company. That was the weird clunky way I came into film.

Adam: Which was Happy Feet?

Bryce: Yes, Happy Feet and Gabriel were my first two film credits.

Adam: They were both out of Australia.

Bryce: Yes, because George Miller is the director of Happy Feet, but he used John Powell, the English composer that lives here. Brilliant composer that he did the score. Elaine Beckett, Craig Beckett, Trackdown is where it was recorded. The whole musical team was in Sydney.

Adam: You've mentioned this name a couple of times, Hans Zimmer. For those who don't follow film at all, Hans Zimmer and his company, Remote Control, he has won two Oscars, four Grammys. He's done endless, memorable, incredible scores, including Inception, Gladiator, Dark Knight. if you're a budding composer coming from Australia, there would be no more desirable roof to be under than someone such as Hans Zimmer.

He's at the top of the pack. Tell us how that happened. Tell us how you go from Sydney to working for Hans.

Bryce: I remember the first night I met him, there was this stuff that happened to me, I wouldn't believe unless it happened to me, but I'd just gotten everyone's dinner and, my car, I'd parked it in an alley to go and pick up a pizza and the thing rolled into a fire hydrant, nearly set the thing off, like in the middle of Santa Monica. This is all in the same night.

Then I go and I go up to the kitchen, I put his dinner out and all this stuff. Then I hear the footsteps coming up the stairs and there he is. He's like, "Hans," and I said, "Bryce." He goes, "Where are you from?" I said, "Sydney, Australia." "What the f*ck are you doing here? You've got a beautiful country." I can really do his voice. I'm just standing there going, "Yes, that's true but I think you know why I'm here. I think that originally because Hans can be, and I understand this, a bit harder on Americans than those from overseas that have had to really work their arse off to get here in many ways.

That's been very general. I think that he liked Australians, he liked Australia. He once said to me that the Australian accent, he thought was the accent of the future when he saw the original Mad Max because that's how everyone was talking in the dystopian future. I've never heard that before.

Adam: Talking about George Miller.

Bryce: Yes, there you go.

Bryce: Basically over the couple of months I was there, I was around him and then I got the job with Ramin. I was Ramin's guy initially. Then how I got out of the Aussie assistant basket with Hans was there's a film called Rango and starring Johnny Depp. This is where dreams come true on the periphery sometimes in Hollywood, which is amazing. They needed a classical guitar for this particular moment and not only classical guitar, but a particular technique called tremolo, where you basically for every thumb stroke, you do these three.

It creates this effect of like you've got the accompaniment and then you've got this melody that's just bubbling across the top. For someone to play classical guitar, that's specific. For someone to play tremolo, that's very specific. I was hoping that enough of his famous friends weren't available, and enough of my friends recommended me for him to go, "Yes. Let's try, Bryce." I did that and he was really happy with it. I think it also helped this cue that they were having some trouble with get across the line with some real audio, real guitar in it.

He's very happy with that. That was a real gratifying moment. Then I became like Bryce, the musician, and I came on different things. There was 14 guitarists on that film. I came in for this is this moment where Rango looks over the desert with his girlfriend and he kisses her for the first time. That's that part. Then Puss in Bootscame up and Rodrigo and Gabriela were doing a focal part of that. I did all the guitars around the periphery and as a classical guitarist, I never was going to pursue a classical concert career or anything.

It was part of the arsenal that I was just trying to build in myself, and here this thing happens just part of the journey that I get to play on a few huge Hollywood films like classical guitar, sitting with my grandmother in Wollongong and my mother listening to classical guitar, watching Puss in Boots and seeing my name in the credits. They're very special moments.

Adam: Absolutely. It was your guitar playing that got you the first sort of creative in with him, but I have to ask, you mentioned at the top of the story that you were serving him dinner. How does one end up serving Hans Zimmer dinner?

Bryce: I didn't cook it for him. I wouldn't have stayed there very long if I did. It's just part of being an intern there. You're responsible for keeping the studio running. Getting coffee, stocking up the fruit and the soft drinks, and going to get the lunches and dinners, sometimes breakfasts, late-night snacks, tequila, whatever they ask for. Even as I said, I had to drive one of the guys there, his daughter, home from ballet, which was just so weird. I'm like, "Have you seen my car? The passenger door rust shut. I can't guarantee it's going to open."

He's like, "Ah, it's fine."

Adam: There it is.

Bryce: I'll get a gift of these pajamas with the right line of pinstripe. The whole thing is like they see how hard you work at that and how much you care. That is where the work ethic is recognized. Hans says that Australians do so much with so little as a compliment. I think, we, by nature work our asses off and don't expect other people to do it.

Adam: Love it. We have to get into the guitar, the seven-octave guitar. I mentioned at the top that you're an inventor and that's certainly one of the things I was referring to. Tell us about that instrument and your story in creating it.

Bryce: When I started my bachelor degree and I was being exposed acutely to all this fantastic music history, because initially I just thought, I just want to get through this stuff and play. I just found myself getting more and more enamored with the music history, whether it's a classical stream or jazz. I just kept on taking as many subjects on as I could. I just realized that the great composers, as we refer to them, never really wrote anything for guitar. Part of it was just because of the nature in a concert hall that it doesn't carry as well and can quickly get absorbed by an orchestra at the time.

The respect was there. Beethoven said the guitar is an orchestra in itself. I just thought, "Man, wouldn't it be great if you could play some uncompromised orchestral pieces of the greats?" My favorite composer is Debussy. I thought, "What would you have to do to a guitar to make that happen?" I just didn't have the facility at the time to come up with that. After I'd done my degree and I was coming into my masters, I started to wonder, "I guess you've got 10 fingers on a piano." I should say, quite often, they do a piano reduction of an orchestral work.

They can sound amazing, like Clair de Lune or whatever. I thought, if I go from that point of departure of a piano, it's like you've got 10 fingers to use on a piano. What about 10 strings? I started with that. Then I talked to a guitar maker in Australia named Gerard Gilet. He's a typical luthier, just say it as it is. I was talking to him about this thing. He's like, "It's not going to work." Then I kept talking to him, like asking questions. I'm like, "I've just got the ideas. You've got the experience." Then he started to see, "If you're thinking like that, maybe that could happen, blah, blah."

Then bit by bitty, he started to get more interested and excited about it. We started working out, taking my ideas and how that was going to work on a practical level. Then at the end, he's like, "All right, let's do it. If it doesn't fly, it's not my fault." Anyway, a few months later, there it was.

Adam: There it is. Has it been used in movies?

Bryce: Yes, it got me a lot of publicity at the time, which is great. Even the new inventors. It's still like people still-- look, we're talking about it now. That circling back to Hans, my first writing, real writing thing with him directly was Ron Howard's film called Rush, about the 1976 race season between Niki Lauda and James Hunt. Hans had heard the guitar, and he's like, "That's pretty cool." Then I ended up writing, because he said, "Go and do something," and I'm like, "What?" "Just go and do something." I'm like, "Okay." I went, and he said, "but only with guitars. We'll figure out the orchestra and the electronica stuff later."

I ended up creating this 37-guitar, six-minute, layered piece that thankfully, Ron Howard got really attached to, which meant I stayed employed. Going in there, when I saw it at the cinema, hearing that guitar and its full range and the sub energy that comes off it, it's like, I'd already had that guitar for a good number of years at that point. It teaches me what I can do. Sometimes it's very inspiring. That was a special moment.

Adam: Yes, absolutely. Going back to 2008, 2009, when you first made the move out to the US, is there anything you would go back and tell yourself, advice yourself?

Bryce: That's a hard one. See, the problem is, I think, if you do that, it could change your trajectory. A lot of times in life, I think you've given what you need to get through at that point. There are exceptions to that, obviously. Especially moving country, that was a huge decision. The tipping point for that was on a personal thingI'd found out in January of 2008, that they, Children House, that they had a spot for me, and starting August. Then in May of that year, my 17-year-old cousin, Jess Jacobs, was tragically killed.

She slipped in front of a train in Melbourne in Melbourne. It was an accident, she was rushing to get the train so she could buy a birthday present for her brother. It was his birthday the following day, it was also Mother's Day the following day. She'd been on Australian TV. She was a great musician, a great little actress. I'd known her since she was just a little kid. I remember Belinda, my wife, at our wedding, in the December of 2007, I was looking at her and she's 17. I'm like, "I'm so excited for your life ahead. She's so cool."

She's not just great at all these things artistically, but she was an old soul in that regard. When this happened, May 10, 2008, one of the things that hit me in the whole arc of it was I just realized how bitter and twisted I'd become at too young an age, in my 20s still. I'm like, she doesn't have a whole life ahead of her. I've got life. I'm still alive. I think it's the only way you can really honor someone that that happens to is to not undermine the opportunities that are out there by your previous disappointments.

I think when August rolled along and coming into America, I thought, "I'm just going to do it. I have to. It's at a point in my life where there's a lot of crossroads, and if I don't do it now, it's just going to get harder." That was a big tipping point.

Adam: There it is. Way to honor Jess Jacobs. She's living on through your work, so that's fantastic. We've really appreciated having you here today.

Bryce: Thank you very much for having me.

Adam: Thanks for joining us today on The Cockatoo Interview. You've been listening to The Cockatoo interview. We are a newsletter that is part of the Pitchhiker Foundation, a 501(c)(3) non-profit. Support us in any way that you support non-profits, but particularly with the media that we create. Share it, enjoy it, and we look forward to catching you on the next edition.